SOCIOECONOMIC FORCES DISCOVERY GROUP MEMBERS

Rob Butera, School of Electrical & Computer Engineering

Susan Cozzens, Office of Graduate Education and Faculty Development

Mike Cummins, Scheller College of Business

Amy Henry, Office of International Education

Mark Hoeting, Office of Information Technology

Bradley Jenkins, Undergraduate Representative, Aerospace Engineering

Gordon Kingsley, School of Public Policy

Jeff Selingo, advisor and author

Bing Wang, Library, Intellectual Property Advisory Offices

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Discovery Group on Socioeconomic Forces was tasked with examining broad social and economic trends that might affect what Georgia Tech chooses to offer next in education, including a look at how Georgia Tech’s business model might be affected by federal and state policy contexts, socioeconomic inequality, globalization, and what is known about the workforce of the future.

With regard to the term business model, we worked with a definition that featured answers to four questions:

- Who does Georgia Tech educate (for example, the “traditional” 18-22 year olds, adult learners)?

- Where does it educate those learners (for example, in Atlanta, online)?

- What does Georgia Tech offer to those learners (for example, degrees, courses, certificates)?

- Who provides the education (for example, tenure track, non-tenure track, or part-time faculty)?

Georgia Tech’s current business model centers on a traditional undergraduate degree offered to traditional on-campus students, with large doctoral student and growing master’s student populations on campus, along with exploding graduate programs online. Except in a few special cases, tuition revenue is not tied directly to enrollment or enrollment growth, but instead used strategically in increments to stabilize base budgets.

With tuition largely out of the university’s control, there is growing attention to programs (both degree and non-degree) that charge market prices for the specialized knowledge the campus has to offer, alongside experiments with much larger, off-campus audiences that pay much lower prices.

Rising tuition levels in both public and private universities in the United States are interacting with stagnating family incomes to make college education less and less accessible for the middle class, and largely out of reach for lower-income families. Georgia Tech’s ability to address financial need is limited by the state law that forbids using tuition or state core funding for scholarships, and therefore limits them to funding raised from private sources.

The percentage of undergraduate students from low-income families has dropped recently at Georgia Tech, part of a trend toward attracting more and more students from affluent families. Alternative educational models that might make a Georgia Tech education more affordable also involve radically different modes of delivery and instructional workforces.

The forces of the global economy have wreaked havoc on the American economy and the domestic student market for much of higher education in the U.S., as well as state appropriations for public institutions. Even as college education becomes relatively more expensive to obtain, the returns from that education are apparently declining. Historically, rising automation led to higher-skilled jobs with better pay. But since the turn of the century, technology has increasingly replaced professional jobs as well, including those that require a college degree, such as lawyers, pharmacists, and lab technicians.

The shape of careers is also changing. Net employment growth in the U.S. since 2005 seems to have come from the “gig economy,” where jobs are temporary and many people work on short-term contracts, where the worker might be employed full-time hours but does not get the benefits and protections of regular employees.

To prepare for these changes, college students must not only acquire expanded knowledge in their education but also strengthen their social skills in areas such as communication, writing, and organizational skills along with customer service, problem solving, planning, and detail orientation.

As the demands of the workplace and higher education shift in the 21st century, policymakers at the state and federal levels are sometimes slow to respond. However, federal policy discussions are taking up financial aid simplification, pursuing the ideal of debt-free college, and reducing the costs of increased regulation that accompany federal financial aid.

Accreditation and quality control, to make sure students get what they pay for from college education, are also on the federal agenda.

Over the past 13 years, Georgia Tech has seen a systematic decline in state funding and a significant rise in tuition revenue. Per capita student funding from state appropriations and tuition combined has been relatively flat for over a decade. The relative share of state dollars vs. tuition dollars has shifted from a 75 percent/25 percent split in 2003 to approximately a 50 percent/50 percent split today.

Despite the relative shift from state appropriations to tuition funding, the state of Georgia still ranks quite well in terms of state support for higher education. Georgia ranked No. 11 in state funding per FTE student in 2014-2015, and above the national average. State legislatures around the country are concerned with financial aid, affordability of college, and student debt, along with completion rates and speeding up time to degree. Some states are adopting performance-based funding.

Our analysis of the context has implications for Georgia Tech:

- The findings of the demographics group point to the fact that competition will be increasingly fierce for traditional U.S. undergraduate students, who are at the heart of Georgia Tech’s traditional core business. The analysis of inequality and employment provided here suggests that more and more families with students who could do very well at Georgia Tech will not be able to afford what we offer. Affordability and access are key issues to address in the next stage of the Commission’s work.

- Second, the employment prospects for the kinds of technical professionals we have traditionally produced are diverging from the past. All high-skill jobs will require high levels of social skills in addition to technical ones, incorporating the advantages of artificial intelligence. Furthermore, the Gig Economy calls for professionals who are flexible and entrepreneurial, while our curriculum is inflexible and leaves little room for choice. To meet emerging educational needs, our curriculum needs to offer opportunities to develop entrepreneurship and other social skills.

- Third, the trends in both demographics and employment suggest strongly that Georgia Tech needs to develop its capabilities for lifelong education. The capability of providing master’s degrees and lifelong education will be an important stabilizing factor in the increasingly dangerous environment of undergraduate education.

- Finally, globalization and the changing U.S. higher education market make recruitment and retention of great faculty much more challenging and expensive. Other U.S. universities are stepping up their efforts to recruit leadership from Tech’s faculty ranks, and universities abroad are recruiting new and established faculty to join their ranks. Georgia Tech needs to offer world-class resources to attract and retain world-class faculty.

Our discovery group returned again and again to an important question: What does it mean to be a leading public technological university? State governments, whether by choice or by necessity, have crafted policies that view higher education as a private good or a quasi-public good.

The Georgia Tech Strategic Plan does not clearly articulate what being a public technological research university means. The discovery group strongly advocates a follow-on project that takes up this question and articulates a Georgia Tech-specific answer.

INTRODUCTION

The Discovery Group on Socioeconomic Forces was tasked with examining broad social and economic trends that might affect what Georgia Tech chooses to offer next in education.

We deferred on the analysis of demographic trends to the Demographics Discovery Group, but decided at the outset to look at how Georgia Tech’s business model might be affected by federal and state policy contexts, socioeconomic inequality, globalization, and what is known about the workforce of the future.

BUSINESS MODELS

With regard to the term business model, we worked with a definition that featured answers to four questions:

- Who does Georgia Tech educate (for example, the “traditional” 18-22 year olds, adult learners)?

- Where does it educate those learners (for example, in Atlanta, online)?

- What does Georgia Tech offer to those learners (for example, degrees, courses, certificates)?

- Who provides the education (for example, tenure track, non-tenure track, or part-time faculty)?

The literature we consulted on university business models and our guest speaker on the topic stressed the importance of identifying the university’s core strengths and achieving success by focusing resources there, putting student needs first, and organizing the educational experience in ways that meet those needs efficiently.

GEORGIA TECH'S CURRENT MODEL

The university’s current model is centered on a traditional bachelor of science degree, offered largely to Georgia or other U.S. students who have just graduated from high school.

What makes Georgia Tech a “technological university” is the predominance of STEM students. While the STEM acronym refers to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, at Georgia Tech engineering and computing majors are the largest groups.

Recruitment of students to other majors is a difficult job, despite the best efforts of undergraduate recruitment and admissions staff and the other colleges. The undergraduate admissions process strives for a balance of 60 percent Georgia residents, 30 percent U.S. out-of-state students, and no more than 10 percent international students.

Application numbers have doubled in the last five years, showing significant demand from all these groups.

A particularly strong link to the state of Georgia is established through the coveted spots Georgia residents compete for in the entering undergraduate class. In fall 2015, 15,142 undergraduates enrolled, including 9,055 from the state of Georgia. There is no plan to grow the size of the undergraduate population.

As a source of revenue, undergraduate tuition is a key factor in the university budget. Tuition is set by the Board of Regents, with the state legislature looking over its shoulder. See more information on tuition in the section below on the state policy context.

Over the past few decades, Georgia Tech has developed the ambition to be more than a technical college for the sons and daughters of the state. Key parts of its emergence at the national and international levels are its research and graduate programs. Only 20 percent of graduate students start out as residents of Georgia, although many who come from other places end up living and working here.

- An integral part of a research university is doctoral education. In Fall 2015, doctoral students numbered 3,281 and represented 13 percent of the student body. About 80 percent were supported as teaching assistants or research assistants under faculty research grants; they thus earned their places on campus through their contributions to education and research missions.

- The primary factor driving the size of doctoral programs is research grants, although the number of teaching assistantships has surged in recent years. The remainder of doctoral students are supported under domestic or international fellowship programs, which attract the best and brightest students to be part of the Georgia Tech research enterprise, with modest subsidies from the university. Half of Tech doctoral students are international; judging by national trends, three quarters of them intend to stay in the United States to work, and two-thirds of them will succeed in doing so.

- Master’s programs have also grown over time. In Fall 2015, 6,517 students were enrolled in master’s degree programs, with 3,733 on campus or at international locations, and an additional 2,784 enrolled in the online Master of Science in Computer Science (OMSCS). Master’s students thus comprised 26 percent of the student body at that time.

- Most master’s students pay their own tuition, which is higher than undergraduate tuition, except in the OMSCS, which charges much less per credit hour (see discussion below). Nineteen master’s programs charge “differential tuition,” above and beyond the base graduate rate; these funds provide for additional services for the students in those programs.

- In addition, a large percentage of master’s students pay out-of-state tuition. Georgia Tech’s leadership would like to see master’s programs grow, both because the degree itself is becoming more necessary in STEM fields and because of their revenue-positive status.

The Georgia Tech curriculum, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, is quite traditional, with some bright spots of innovation as identified and described by the Peers Discovery Group. The undergraduate curriculum is characterized by core requirements set by the state system and heavy course loads in each major, with little space for electives.

Most master’s programs are also highly structured, and doctoral programs typically require at least a year of coursework, sometimes two. There are few cross-school or cross-college majors, particularly at the undergraduate but also at the graduate level, although most of the new programs over the last few years have been offered across schools or colleges, almost all at the graduate level.

A few older majors that fell below minimum sizes have been merged with larger related degrees, and the schools that support them have been combined.

Georgia Tech has a large continuing education enterprise, offering short courses and certificates in specific areas of campus technical strength to adult learner audiences. In FY 2015, 22,128 unique individuals took a class with Georgia Tech Professional Education (GTPE), of whom 18,248 were engaged in professional development.

Further, 118 countries and nearly 3,000 organizations were represented in the enrollments. In head count, the number of professional education learners is approaching the number of traditional residential students. This enterprise pays its own costs and generates direct revenue for the academic units that participate.

Forty percent of every dollar collected goes back to faculty or units, for a total of nearly $13 million in FY 2015. The professional education enterprise also pays other fees, debt service, and technology licenses that benefit the rest of the Institute.

SOME EXCEPTIONS

A few types of degrees operate on different or complementary financial models, for example:

- The Executive Master of Business Administration charges premium tuition and provides what it sees as a premium educational experience, with a core delivered by tenure track faculty and other elements of the degree offered by non-tenure track faculty with experience in business who are evaluated primarily on their teaching effectiveness.

- Professional Master’s (PM) degrees cater to working professionals with a hybrid model, involving cohorts, limited time on campus, and a majority of coursework online. These programs charge the distance education tuition rate, which is close to graduate out-of-state rates.

- The Online Master of Science in Computer Science (OMSCS) charges very low tuition (30 percent of the in-state graduate rate and 15 percent of the out-of-state rate) for large-enrollment courses offered in a format that resembles MOOCs (massive, open, online courses). A major firm provided a sizeable grant to underwrite the development of the courses, which require significant initial investments of time from both the faculty member involved and a staff of supporting instructional designers. Once developed, the courses can be offered to hundreds of students at a time at a relatively low cost. The faculty who develop the courses share in the revenue.

IN SUMMARY - BUSINESS MODELS

Georgia Tech’s current business model centers on a traditional undergraduate degree offered to traditional on-campus students, with large doctoral student and growing master’s student populations on campus.

Except in a few special cases, tuition revenue is not tied directly to enrollment or enrollment growth, but instead used strategically in increments to stabilize base budgets.

With tuition largely out of the university’s control, there is growing attention to programs (both degree and non-degree) that charge market prices for the specialized knowledge the campus has to offer, alongside experiments with much larger off-campus audiences that pay much lower prices.

SOCIOECONOMIC TRENDS - CHANGING ECONOMICS

The two and a half decades after World War II were a golden era for the U.S. economy and the American higher education system. The GI Bill allowed returning veterans to go to college for free, and the fast-growing, post-war workforce quickly absorbed them.

The children of that generation, the Baby Boomers, along with the onset of the Cold War in the 1960s, ushered in unprecedented growth in higher education spending and enrollments.

But the economic effects of World War II ran out of steam in the 1970s. That’s when the U.S. began a generations-long transition away from manufacturing to an information economy interconnected with the rest of the world. In 1970, factory work accounted for 25 percent of jobs nationwide. Today, it accounts for just 10 percent.

The sharp acceleration in globalization since the turn of the century, especially with the entry of China and its huge labor reserves into the W.T.O., contributed to further declines in U.S. manufacturing jobs, stagnant wage growth across the board, and increasing inequality.

Today, a typical production or nonsupervisory worker earns about 13 percent less than in 1973, after adjusting for inflation, even as productivity has risen by 107 percent. [1] Overall, median per capita income in the U.S. has basically flat-lined since 2000, when adjusted for inflation.

The typical American family makes slightly less than a typical family did 15 years ago. And while many products have become less expensive in that time, the price tag of three of the biggest expenditures made by middle-class families — housing, college tuition, and health care — have increased much faster than the rate of inflation[2].

To put this loss of buying power into perspective, 30 years ago, in the fall of 1986, tuition and fees for an out-of-state student for one academic year, adjusted to 2016 dollars, were $10,277.

For the Fall 2016 semester, comparable tuition and fees are $12,212 for an in-state student and $32,404 for an out-of-state student.

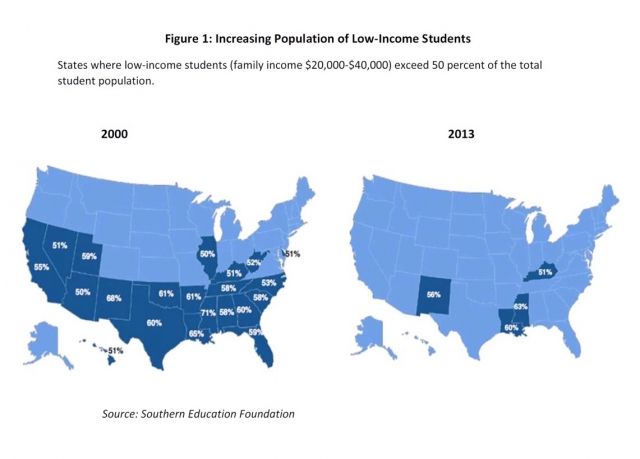

In a 2015 report, the Pew Research Center noted that the American middle class is on the decline. Over the last 40 years, the middle class went from a clear majority to a group that is now matched in size by lower- and upper-income households. “The biggest winners since 1971 are people 65 and older,” the report said. “The youngest adults, ages 18 to 29, are among the notable losers with a significant rise in their share in the lower-income tiers.” (Figure 1)

Even as many colleges and universities discount their tuition more and more each year — the average discount rate was 48 percent for freshmen in 2014 — family incomes are simply not keeping pace.

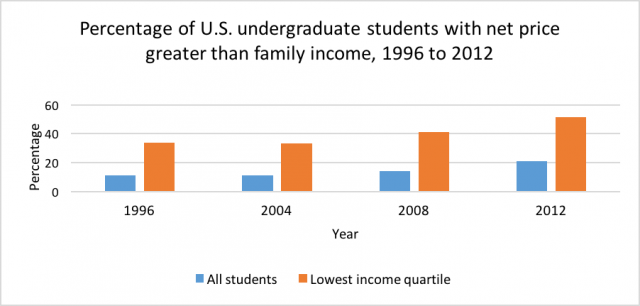

Today, one out of every five families in the U.S. that sends a student to college pays 100 percent or more of their annual income to cover the net price of college. Because even the discounted tuition rate outstrips their ability to pay, those families need to borrow or use savings to cover tuition bills.

The situation is even worse for students in the lowest income quartile. Among those families, half pay 100 percent or more of their annual income to cover the net price of college. (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rising Net Price of Tuition (Source: National Postsecondary Student Aid Study)

INEQUALITY, ACCESS, AND AFFORDABILITY AT GEORGIA TECH

For Georgia Tech, the resident cost of attendance for 2016-17 is $27,420, with approximately $12,000 of that going to tuition and fees. According to Paul Kohn, vice president for Enrollment Management, it is the costs beyond tuition and fees that are a hardship for many Georgia families.

Currently, 68 percent of Georgia Tech students who are residents of the state qualify for need-based financial aid. And yet, the average amount of Georgia Tech financial assistance to all entering first-year undergraduate students mitigates only about a quarter of student need. In 2015-16, there was $45 million of unmet Georgia resident financial need.

Between 2011-12 and 2013-14, Georgia residents nearly doubled their debt to private lenders. Federal borrowing also increased, although much less significantly. The average Tech undergraduate student graduates with $24,000 in debt, far above the average and far above those of our private peers.

Great students who have been admitted are choosing other universities, often outside the state, because those universities are able to offer financial aid packages that make the out-of-pocket cost to students and their families much lower.

Georgia Tech is not fulfilling its mission to the public when residents of the state leave for college because other universities better meet their financial needs. In the future, Georgia and non-Georgia residents will have even higher levels of need as the costs of attendance continue to rise and the incomes of Georgia and U.S. families continue to stagnate or decline (when adjusted for inflation).

One strategy for providing scholarships or tuition discounting to students is to use tuition dollars collected. This is a strategy used by many, including the state of North Carolina to fund its Carolina Covenant program (similar to Tech Promise). Legislation in the state of Georgia prohibits the use of tuition dollars or state funds for scholarships.

Therefore, the only means of increasing scholarship support is by raising funds from private donors and entities.

Another barrier to enrolling more socioeconomically diverse residents is the public perception of Georgia Tech. Many prospective students and their families think Georgia Tech has only engineering and computer science degrees, and many more think that grading is so harsh that they will certainly lose their Zell Miller or HOPE scholarships. Their fears are not unfounded.

While 80 percent of Georgia-resident freshmen enter as Zell Miller Scholars and 18 percent enter as HOPE scholars, only 62 percent of Zell Miller scholars maintain eligibility for their second year (20 percent also lose Miller, but stay eligible for HOPE, which provides approximately $1,500 less per semester). Fifty-five percent of freshmen who enter as HOPE recipients remain HOPE eligible for their second year.

Some evidence that we are heading toward an elitism that undermines our public mission lies in the percentage of students who are eligible for federal Pell grants. In Fall 2014, 18 percent of the undergraduate class was Pell grant eligible. That number was the lowest in five years. The decline suggests that we are increasingly successful at middle class ($60-$120k/year) recruitment but less so among the poorest.

Changing socioeconomic conditions may not continue to support the old models of education that are centered around classrooms, semesters, and traditional college-aged students. A study for the Gates Foundation that involved Georgia Tech faculty sought out alternative models designed to generate education services at a low cost.

These models often used a completely different set of workers engaged in the functions like curating material, and instructional design of student interfaces with curriculum, assessments, and instruction. The faculty role was very different in this type of model, which also focused on quality control, student advisement, and instructional presentation.

VALUE OF BACHELOR'S DEGREES

The trends in globalization have acted as a double-edged sword for higher education. On one hand, increasing internationalization has meant that American colleges and universities are more popular around the world than ever before, and more accessible to international students and their families. The number of undergraduate students traveling abroad to obtain a degree has increased by nearly 7 percent since 2005 — thanks in large part to Asian students studying outside Asia — following growth that hewed closer to the 4 percent mark in the prior 30 years. [3]

At Georgia Tech, the number of international students has increased steadily over the last two decades, with most of the growth in international student enrollment happening at the graduate level. In 1990, 1,088 international students were enrolled at Georgia Tech. By 2015, the number reached 5,493, placing the Institute among the 25 U.S. universities hosting the largest number of international students. Most of those international students participate in grant-funded research, and they are critical to accomplishing the research mission of the Institute.

While globalization has added international students to U.S. universities, the forces of the global economy have wreaked havoc on the American economy and the domestic student market for much of higher education in the U.S., as well as state appropriations for public institutions. Even though the unemployment rate has dropped significantly since the Great Recession of 2008, wages have not rebounded for most workers.

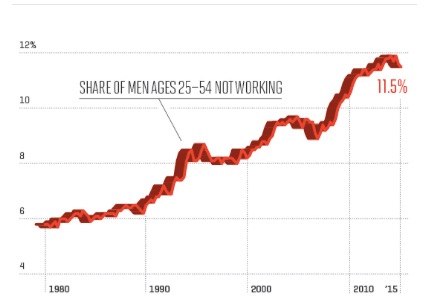

What makes the economic picture even more difficult to predict going forward is a job market that doesn’t seem to be following any historical trends. For one, fewer men in their prime working years are employed, a group that has mostly found full-time work in the past (Figure 3). The common explanation by economists is that machines have replaced people in low-skill jobs, and many of those positions were held by men. This group includes the fathers of many potential Georgia Tech students.

Figure 3: Employment of Men in Prime Working Age (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve)

Historically, rising automation led to higher-skilled jobs with better pay. But since the turn of the century, another anomaly that makes the job market difficult to forecast is that technology has increasingly replaced professional jobs as well, including those that require a college degree, such as lawyers, pharmacists, and lab technicians.

The result? Nearly half of recent college graduates are underemployed, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, meaning the jobs they can get don’t require a bachelor’s degree.

“Having a B.A. is less about obtaining access to high paying managerial and technology jobs and more about beating out less educated workers for the barista and clerical job,” according to a widely cited 2014 research paper by three economists, Paul Beaudry, David Green, and Benjamin Sand.

Their study found that demand for college-educated knowledge workers has slowed as the tech revolution has matured. And it suggested that this situation may be the new normal — where the bachelor’s degree is needed to get any job, not just a high-skilled, high-wage job.

Underemployment is less of a problem for students who earn degrees in engineering and computer science, which make up the vast majority of Tech undergraduate degrees awarded. What is critical for all graduates is the ability to keep learning, changing, and growing as the job market changes.

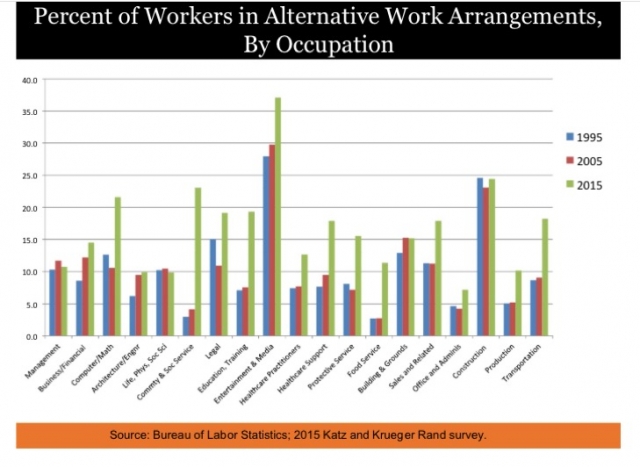

More recent research by Lawrence Katz at Harvard University and Alan Krueger at Princeton University (and former economic advisor to the Obama Administration) has found that all the net employment growth in the U.S. since 2005 seems to have come from what they call “alternative” work.

This type of work, often referred to as the gig economy, is anything that is temporary, including contract workers who might be employed full-time hours, but do not get the benefits and protections of regular employees.

The number of contract workers, according to the pair of researchers, increased from 14.2 million in 2005 to 23.6 million in 2015, across all occupations (Figure 4). “As of late 2015, we had not yet quite fully recovered from the huge loss of traditional jobs from the Great Recession,” Katz and Krueger wrote.

Indeed, a number of economists and technologists are beginning to wonder whether a longstanding tenet in the race between education and technology will continue to hold true in the future — that educated adults will always be able to keep one step ahead. Former Treasury Secretary and Harvard University President Lawrence H. Summers calls the issues of automation of white-collar work “the defining economic feature of our era.”

Adds Bill Gates: “Twenty years from now, labor demand for lots of skill sets will be substantially lower. I don’t think people have that in their mental model.” [4]

One study from Oxford University in 2013 predicted that nearly half of American jobs were at risk of being displaced in the future by automation and artificial intelligence (Figure 5).

There will still be jobs, of course, but increasingly the economy will be largely bifurcated into two groups — one that is highly educated and works complementing technology and the other that will work low-skill service jobs that can’t be easily or cheaply replaced by a computer.

Figure 4: The Gig Economy

Figure 5: Loss of Jobs to Automation

The prospects for long-term unemployment and underemployment for large swaths of the U.S. population in their prime working years could have devastating consequences for the consumption side of the economy, trends we’re already beginning to see.

The top 5 percent of households in terms of income in the U.S. account for some 40 percent of spending.

Not all economists are as dire in their outlook for future employment as are Summers and Gates. MIT’s David Autor maintains that even in an era of increased automation, humans still need to augment technology, particularly for jobs that require flexibility, judgment, and common sense. “Tasks that cannot be substituted by computerization are generally complemented by it. This point is as fundamental as it is overlooked,” Autor wrote in 2014. [5]

SOCIAL SKILLS

This augmentation economy demands strong technical skills, but almost equally social skills, a term associated with how co-workers get along with each other, communicate, and work in teams.

When Burning Glass, a company that mines job ads, analyzed the requirements listed in 20 million postings across all industries in 2014, it found that people skills appeared far more often than any technical skills. “It reflects a perception that students are coming to the market less job ready with these skills,” said the CEO of Burning Glass, Matt Sigelman.

Twenty-five skills appeared in three out of every four job advertisements analyzed by Burning Glass, no matter the industry. Virtually every job posting included in its top five communication, writing, and organizational skills.

Writing, for example, was an important skill even in information technology and health care jobs. Other competencies frequently requested across industries were a combination of social skills — customer service, problem solving, planning, and being detailed-oriented — as well as very specific technical skills — Microsoft Excel and Word.

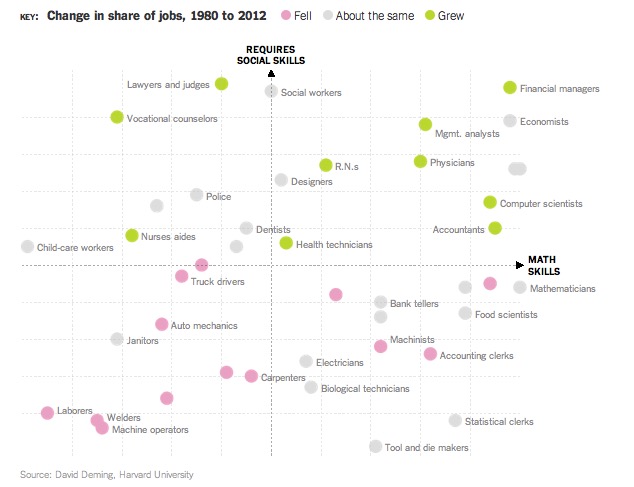

Occupations that require strong social skills are growing much more than others, according to research by Harvard University’s Robert Deming. The occupations that have shown consistent wage growth since 2000 require both cognitive and social skills, such as doctors and engineers. Jobs that require strong social skills have also grown, such as lawyers and child care workers (Figure 6).

Deming’s research has found that where education mimics the modern workplace is in preschool, where children move from projects to play and the most important skills are curiosity, sharing, and negotiating.

But eventually that style of learning is replaced by the teaching of technical skills, typically in lecture format, and with less peer interaction. A mix in education of the teaching of both technical and social skills is critical, Deming argues in his research.

Figure 6: Growth in Jobs Demanding Social and Cognitive Skills

The issue now for colleges and universities is how best to prepare students for the future workplace, given that social skills are rarely emphasized in the traditional curriculum.

At Georgia Tech, calls for these skills are not new. In fact, Georgia Tech alumni surveys have been reflecting for decades the demand for more communication and management skills to be incorporated in the educational experience at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

Globalization and domestic socioeconomic trends have led to a workplace and a market for goods and services that is more diverse than ever. The workplaces that our graduates will move into will be filled, as the campus is, with people from different economic backgrounds, races, ethnicities, religions, nationalities, and all variations of identity.

We can build preparation for that workplace into their student experience, but the task requires conscious attention and support and training for faculty.

THE FEDERAL AND STATE POLICY CONTEXTS

Federal

Even as the demands of the workplace and higher education shift in the 21st century, policymakers at the state and federal levels are often slow to respond.

The main federal vehicle for higher education policy, the Higher Education Act, has not been reauthorized since 2008. Most significant changes to federal higher education policy in recent years have occurred either through other legislation or through regulatory changes from the U.S. Department of Education.

Congressional observers do not see a major rewrite of the Higher Education Act coming anytime soon. A new administration in 2017, regardless of party, is unlikely to make the law a high priority in a crowded legislative calendar. What is more likely is that policy changes will continue to happen through other legislation or rewriting regulations. Among the key changes under discussion:

• Financial aid simplification. A proposal to eliminate the 10-page, Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) has broad bipartisan support because it reduces paperwork and potentially could encourage more low-income students to enroll in college. Researchers have found that such students are overwhelmed by the amount of information requested in the 100-plus questions on the current FAFSA. That document would be replaced with a postcard that has just two questions: family size and household income.

In addition, Congress is weighing proposals to streamline the plethora of federal student-aid programs into one loan program for undergraduates, one for graduate students, and one for parents.

• Debt-free college. President Obama’s free community college proposal in 2015 and the 2016 presidential campaign have pushed the idea of free college to the forefront of policy discussions in Washington. While it’s unlikely that free college will become a reality no matter who controls the White House and Congress, calls to rein in the growing volume of student loan debt in the U.S. — which now stands at $1.2-trillion — are expected only to increase.

This push is likely to come in the form of incentives from the federal government that encourage states to maintain taxpayer appropriations to public colleges and universities at certain levels and invest more in need-based aid.

• Borrower Defense to Repayment. In the 1993 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, Congress added a small provision to the law that allowed students to have their federal loans forgiven if they were victims of fraud. For much of the two decades since the provision was passed, it has been largely ignored. That’s until 2015, when Corinthian Colleges collapsed after federal officials found that the for-profit chain of schools had fraudulently inflated its job placement rates.

Now, federal officials are clarifying the rule that could have a far-reaching impact beyond the for-profit sector. Under the proposed rules, which would go into effect in 2017, any statement or omission “with a likelihood or tendency to mislead under the circumstances” forms the basis for student claims. And the Department of Education has the authority to put that cost back onto the school. The rule’s broad definition of what constitutes a misrepresentation in marketing to students and its new requirements for the financial stability of institutions, in particular, could pose risks for traditional non-profit colleges and universities.

• Reducing costs of increased regulation. A study commissioned by Vanderbilt University in 2015, and conducted by the Boston Consulting Group, found that the university spends almost $150 million — 11 percent of its nonclinical expenses — complying with federal rules each year.

The study followed on the heels of a federal task force that was created by four senators in 2013, and led by Brit Kirwan, of the University System of Maryland, and Nicholas Zeppos, of Vanderbilt University.

A report issued by the task force identified 59 regulations of concern and 10 rules that it found “especially problematic,” including those governing accreditation, campus crime, consumer information, distance education, and student aid.

While there is support among many lawmakers in Congress to reduce the regulatory burden on higher education, any changes are likely to come with strings attached that require colleges and universities to use the cost savings to reduce their tuition.

• Accreditation and quality control. How quality control is governed in higher education through the existing system of regional accreditors is likely to undergo some changes in the coming decade.

In recent years, the system’s self-regulation has come under increased scrutiny as questions have been raised about colleges that continue to operate with low graduation rates or that produce graduates deep in debt and without any job prospects.

In June 2016, an advisory board within the Department of Education voted to strip one of the largest accreditors in the country of federal recognition because of its lax oversight.

While there is widespread agreement among college officials and policymakers that the current accreditation system is broken, there is less consensus on what should replace it. In 2015, the Department of Education put in place a pilot program that allowed federal grants and loans to flow to coding boot camps and other education-tech companies that provide short-term training and teamed up colleges and universities.

A key part of the experimental program was adding third-party “quality-assurance entities” to audit the results as a way to determine if new accreditation models might emerge.

Another group taking a larger role in quality control is employers. They are doing so by defining quality institutions through their tuition-assistance programs.

Some 71 percent of employers offer tuition benefits to their workers, according to Deloitte, and spend nearly $22 billion on the benefit annually. Most employers offer a flat-rate benefit each year and have long controlled how that money is used — for classes related to a person’s job or other positions in the organization.

Now, employers want more oversight in where their dollars are used. Companies are picking one or just a small group of colleges where employees can use their educational benefit. JetBlue, for instance, works with just seven pre-approved providers.

Starbucks has partnered with Arizona State University to allow employees in the U.S. to complete their degrees for free. And Anthem Inc., one of the nation’s largest health benefits companies, has joined with Southern New Hampshire University to offer free self-paced associate’s and bachelor’s degree programs for their employees.

In making these exclusive deals, the companies are often not only negotiating lower tuition prices than they would pay if the employees enrolled on their own, but they are also making judgments about quality. Like students worried about wasting their money at a sub-par college, employers are also trying to reduce their risks.

Given how much money employers spend on tuition benefits, where companies decide to spend their dollars has ripple effects.

On other matters related to Congress, research funding seems to have bottomed out, but is expected to increase only modestly. The November 2015 federal budget agreement will support some increase in federal grants in 2016 and 2017, likely in the 3 percent range.

Research funding has been relatively flat over the last two years, with a heightened competitive environment resulting in declining research funding for some universities. Universities are increasingly pursuing non-federally sponsored research. This typically does not provide the same level of funding for the indirect costs of doing research.

As a result, more research universities will fund these indirect costs from their own budgets or by seeking greater philanthropic support for research.[6]

Congress is likely to continue to push for more transparency in college and university endowments — how the money is spent, the fees paid to money managers, and the share of the endowment going toward student aid. The demands come amid growing public debate over endowments’ tax-exempt status and the concern that federal tax policy favors wealthy institutions.

This is a perennial issue in Congress, although lawmakers rarely act beyond sending questionnaires to college officials and holding hearings. And lately, their scrutiny has been focused only on private institutions.

Congressional oversight is also likely to continue on intercollegiate athletics, specifically focused on the tax-exempt status of the NCAA, the impact of concussions on young athletes and their general welfare, and limitations on scholarships.

Over the past decade, Congress has made several inquiries into the NCAA and college sports, but none of them have led to changes. Bills have been introduced in recent years to create a presidential commission to study various issues around college athletes, but that has stalled in committee hearings.

Trends and Impact in State Funding

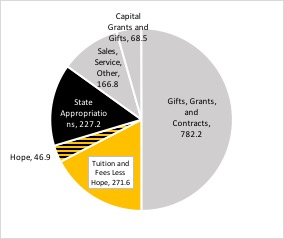

Georgia Tech had a budget of approximately $1.5 billion in FY 2015; of that total, approximately $545 million is state appropriations and tuition dollars.[7]

These two categories of income support the majority of the educational mission of Georgia Tech. Within the category of tuition, approximately $46.9 million is from the HOPE scholarship program, which is separated out from the tuition figure to highlight its role. Figure 1 illustrates the major categories of revenue for Georgia Tech.

Any funding for capital improvements, such as buildings, is referred to as Capital Grants and Gifts. The relative amounts in Figure 7 are not too different from trends of other major public research universities.[8]

Figure 7: Revenue Sources to Georgia Tech in FY2015 (amounts in millions of dollars)

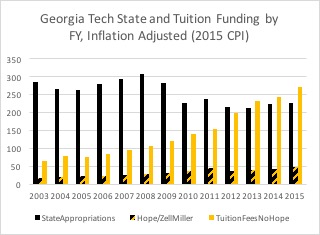

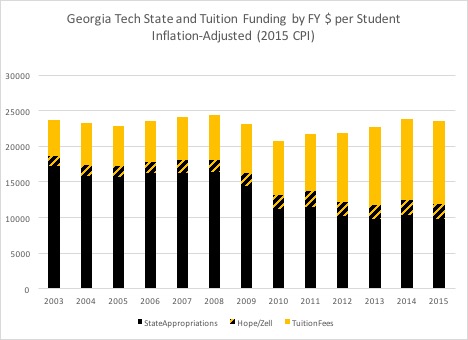

Over the past 13 years, Georgia Tech has seen a systematic decline in state funding and a significant rise in tuition revenue. Figure 8 illustrates these trends, inflation-adjusted to 2015 dollars.

However, during this same time period, total enrollment at Georgia Tech increased by 50 percent, with the bulk of that increase occurring at the graduate level (where about 40 percent of students are international). When the data in Figure 8 is adjusted to a per capita student basis, the trends are quite pronounced (Figure 9).

Figure 8: State and tuition funding and HOPE/Zell Miller scholarships income by FY (amounts in millions of dollars)

Figure 9: Per capita student funding in 2015 dollars from state appropriations, Tuition and Fees, and HOPE/Zell Miller scholarships.

- Per capita student funding from state appropriations and tuition combined has been relatively flat for over a decade.

- The relative share of state dollars vs. tuition dollars has shifted from a 75 percent/25 percent split in 2003 to approximately a 50 percent/50 percent split today. Fifty percent of the amount in 2015 in Figure 3 was tuition dollars from non-HOPE/Zell Miller sources.

This analysis is overly simple. Not all state appropriations directly support the educational mission, and other revenue sources (e.g., sponsored research) directly or indirectly support both infrastructure and faculty that are also engaged in education.

Thus, it is difficult to compare these numbers to more rigorous studies that look at expenditures and appropriations at a more detailed level. Nevertheless, the trends identified are clear, and these trends are not unique to Georgia Tech. The Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia itself has made presentations[8] documenting a shift from a 75/25 to a 50/50 split in state vs. tuition dollars in supporting educational efforts at state colleges and universities.

Nationally, for public four-year universities, the state appropriation revenue per full-time equivalent student has dropped from $7,848 in 2007-08 to $5,905 in 2014-15 in 2015 dollars.[7]

Despite the relative shift from state appropriations to tuition funding, the state of Georgia still ranks quite well in terms of state support for higher education. Georgia ranked No. 11 in state funding per FTE student in 2014-15, and above the national average.[9]

Trends in State Policies

In 2015, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) tracked trends in legislation for higher education in the states. The top themes included:

- Affordability (mandated tuition reductions, requirements for using open-source course materials, expansion of savings plans)

- Financial Aid (expansions in need-based programs)

- Increasing Educational Attainment (including completion performance metrics in state funding formulas now expanded in some form to 30 states)

- Student Loan Debt (tax credits, tuition caps, stabilization funds)

- Workforce Development (expansion of apprenticeship and internship programs)

- Campus Safety (sexual assault rules and regulations, gun accessibility or gun control)

- Dual Enrollment (accelerated coursework, mastery demonstration as course substitute)

Additional trends noted by NCSL include:

- Performance-Based Funding for Higher Education among the States: Funding formulas among states to reward higher education for degree completion. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, Georgia is considered an “in transition” state with performance measures moving to “student progression, degrees conferred, success of low-income and adult learners, and institution-specific measures to account for different missions and strategic initiatives.” Other states have moved more aggressively on performance-based formulas aimed at degree completion.

- Speed Up Time to Degree: Increased number of students pursuing advanced credits, International Baccalaureates, and accelerated dual learning programs. For example, in 2014-15, there were 108,301 students enrolled in AP classes in Georgia, and 82,936 completed AP examinations (according to the College Board).

IMPLICATIONS FOR GEORGIA TECH

Our analysis and discussions draw on the findings of other Discovery Groups (particularly Demographics and Peers), and lead to implications in areas that others are covering as well (Future Learning Needs and Future Pedagogy). This section connects findings from all the Discovery Groups to the questions of the business model.

First, the findings of the Demographics Group point to the fact that competition will be increasingly fierce for traditional U.S. undergraduate students, who are at the heart of Georgia Tech’s traditional core business.

The analysis of inequality and employment provided here suggests that more and more families with students who could do very well at Georgia Tech will not be able to afford what we offer, for two reasons. On the one hand, they will need more financial aid, and on the other hand, we will be unable to meet that need because of the prohibition of using state funds for scholarships.

Success in our core business will therefore become increasingly risky, unless we resign ourselves to attracting the second tier of technically talented students from affluent families. A future of this sort undermines our public service mission.

Second, the employment prospects for the kinds of technical professionals we have traditionally produced are diverging from the past.

All high-skill jobs will require high levels of social skills in addition to technical ones, incorporating the advantages of artificial intelligence. We do not have measures of the extent to which these skills are incorporated into a Georgia Tech education at any level, B.S., M.S., or Ph.D.; but the reputation of the campus does not lie in this direction.

Furthermore, the Gig Economy calls for professionals who are flexible and entrepreneurial, while our curriculum is inflexible and leaves little room for choice.

Entrepreneurship is sometimes defined narrowly in business terms, and treated as an add-on. The Future Learner and Future Pedagogy Discovery Groups are further characterizing the baseline and changes needed in “the Georgia Tech education” to meet the needs of our future graduates at all levels.

Failure to make the appropriate changes would further undermine our ability to compete for the dwindling numbers of high school graduates who are adequately prepared both academically and economically to come here.

Third, the trends in both demographics and employment suggest strongly that Georgia Tech needs to develop its capabilities for lifelong education. Not only our graduates, but indeed generations of students emerging with higher education degrees from all institutions, will need many opportunities to continue to build their skills and acquire new knowledge throughout their lifetimes.

Master’s degrees will play an increasingly important role, but the opportunities also need to appear in formats other than degree programs. Georgia Tech is experimenting with these kinds of offerings. This capability will be an important stabilizing factor in the increasingly dangerous environment of undergraduate education.

Finally, globalization and the changing U.S. higher education market make recruitment and retention of great faculty much more challenging and expensive.

Start-up costs for research faculty in STEM disciplines are very high, both for Ph.D.s seeking their first tenure track position and for established faculty.

Other U.S. universities are stepping up their efforts to recruit leadership from Tech’s faculty ranks, and universities abroad are recruiting new and established faculty to join their ranks, particularly in a few countries where investment in higher education is exploding.

ARTICULATING GEORGIA TECH'S PUBLIC MISSION

Our discovery group returned again and again to an important question: What does it mean to be a leading public technological university?

State governments, whether by choice or by necessity, have crafted policies that view higher education as a private good or a quasi-public good. What this means is that political leaders are unclear about their vision for what public higher education should be.

On the one hand, we are put in a position of covering declining state support with tuition dollars.

On the other, we experience greater involvement from the state on a wide range of issues, as have other state universities. Examples (drawn from around the country, not necessarily Georgia) include performance funding, limits on using state funds for need-based aid, setting percentage requirements for in-state enrollments, and sexual assault rules and regulations, as well as reducing barriers to gun possession on campus (to name a few).

The Georgia Tech Strategic Plan does not clearly articulate what being a public technological research university means. The discovery group strongly advocates a follow-on project that takes up this question and articulates a Georgia Tech-specific answer.

SCENARIOS FOR THE FUTURE

The fictional scenarios below illustrate some of the possible directions that Georgia Tech might take.

Elite. The aspiration is to be a public Cal Tech, Carnegie Mellon, or MIT. The undergraduate student body stays at its current size and the graduate student body grows to become a majority. Revenues generated at the graduate level allow reductions in the student/faculty ratio.

But because of the limited resources for financial aid, both undergraduate and master’s student populations are drawn increasingly from affluent families and privileged educational environments. Since competition for these students is increasing, success in this model depends on employability and salary levels for graduates and an upward trajectory in research reputation.

Curriculum reform that reduces fragmentation reduces costs and allows for more competitive student/faculty ratios. To ensure the quality of the educational experience, creative teachers are recruited into a new tenure track for educational innovators.

Even research track faculty pay equal attention to innovative aspects of the undergraduate curriculum along with doctoral education, while the growth in master’s programs is enabled by non-tenure track faculty who bring practical experience into the curriculum at a lower unit cost.

Upward Pathway. In order to increase the number of students from disadvantaged backgrounds who are prepared for a Georgia Tech education, the university focuses on innovation in STEM education in Atlanta and Georgia schools in low-resource areas, leading the nation in its effectiveness in these environments.

A new interdisciplinary research institute is established in STEM educational research. Connections to individual students provide inspiration for donors (both individual and corporate) to expand scholarship programs that entice the students to the Georgia Tech campus, extending to support for their master’s-level education through BS/MS degrees.

The university’s reputation in the state grows as it enriches the Georgia workforce, in addition to contributing to economic development through research and extension programs. The public mission expands beyond the state, and Georgia Tech leads in identifying and solving global problems.

Industry on Steroids. Georgia Tech draws on its traditional strengths in connections to industry to create its competitive advantage in the STEM education space.

Firms fund a wide range of campus functions: undergraduate and master’s-level scholarships (with recipients selected by the firms based on people analytics), certificate programs that upgrade their employees’ skills, communications and teamwork specialists to make sure social skills are built into the curriculum, etc.

For students, return on investment continues to rise because of the substantial industry subsidies and is a significant recruitment advantage for the campus, counteracting the low levels of financial aid with the promise of future income. Majors that are not of interest to corporate sponsors are dropped, and incoming students are encouraged to take their liberal arts and sciences courses before they arrive or at other local colleges in order to concentrate resources on the areas that appeal to firms.

Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts and the College of Sciences eventually revert to the service divisions they were 30 years ago.

Global Presence Online. In addition to maintaining vibrant on-campus degree programs, the university expands its leadership position in providing low-cost, high-quality online education to a diverse set of learners. Modules are offered as well as degrees.

Connections to mid-career adults through these programs enrich the campus environment for BS and MS students, and increase their employability and salaries. Tenure track faculty aspire to be online rock stars with thousands of followers; success in online instruction becomes a key criterion in tenure decisions.

The cost of delivering a Georgia Tech degree drops by incorporating some of these online offerings into degree programs.

Full Speed Ahead. Georgia Tech remains the best of the public technological universities, offering a bargain-priced standard STEM educational experience at a tuition level set largely by state politics.

The occasional faculty entrepreneur starts an innovative educational project with external funds or sweat equity, and the successful ones eventually find institutional funding and are featured in descriptions of the on-campus educational experience for recruitment purposes.

Most faculty avoid change in the way they teach because educational creativity takes time away from grants and publications and receives little attention in the promotion and tenure process. Growth in existing programs brings no additional resources under the incremental budgeting system.

However, tenure track faculty members nonetheless invent creative new doctoral programs at a rate of one or two a year to attract more interesting doctoral students to contribute to their exciting research, and the university invests in these programs in order to retain high-powered research faculty. The research culture rejects professional (“terminal”) master’s programs like foreign bodies; successful ones thrive on the margins, taught by non-tenure track faculty or producing revenue from which some portion is distributed directly to faculty, schools, or colleges.

After a decade or two of this status quo, the cost of offering traditional STEM degrees exceeds the combination of state appropriations and tuition revenues and the university phases out on-campus degree programs in order to avoid bankruptcy.

Tenure becomes irrelevant, as faculty are hired for research and paid supplemental salary for any teaching. After research operations move to Marietta, the sale of the Midtown campus funds a substantial endowment to support innovation in online offerings.

The Discovery Group is pleased to be working together with campus colleagues to make choices among the many options open for “Creating the Next in Education” at Georgia Tech.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] Ford, Martin. Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future.

[2] Pew Research Center. 2015. “The American Middle Class Is Losing Ground: No longer the majority and falling behind financially,” Washington, D.C. December. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/12/09/the-american-middle-class-is-losing-ground/

[3] OECD and Open Doors (http://www.iie.org/Research-and-Publications/Open-Doors#.V50TkpMrJPM)

[4] Geoff Colvin, “In the future will there be any work left for people to do?” Fortune. June 2, 2014.

[5] David H. Autor, “Polanyi’s Paradox and the Shape of Employment Growth,” MIT, NBER and JPAL, September 3, 2014.

[6] Moody’s Investors Service. 2016 Outlook for Higher Education, December 2, 2015.

[7] Georgia Tech Annual Financial Reports, retrieved from http://www.fin-services.gatech.edu/financial-reports

[8] National Center for Educational Statistics, retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_333.10.asp

[9] Sandy Baum and Martha Johnson, Financing Public Higher Education: Variation Across the States. The Urban Institute, November, 2015. Retrieved from http://urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/2000501-Financing-Public-Higher-Education-Variation-across-states.pdf