The Georgia Institute of Technology entered the 20th century as a well-regarded, regionally significant, technological university. Founded in the Reconstruction era to promote industrial development and devoted to undergraduate training in engineering, commerce, and the industrial arts, the Institute distinguished itself in the Southeast over the next hundred years, climbing to national prominence in the years between 1975 to 2000.

Georgia Tech began the 21st century as a defining international force in higher education. Distinguished by research achievement, economic impact, global reach, an aspirational mission, and an academic reputation that rivals elite institutions, the Georgia Tech of 2016 consistently ranks among the best universities in the world.

The university’s ascendance is widely admired and its approach to institutional innovation — a combination of inspired leadership, a faculty committed to excellence, students with distinguished achievements post-graduation, and a region that broadly supports Georgia Tech’s aspirations in higher education — is much imitated.

Georgia Tech’s mission to define the technological university of the 21st century is not a strategic boilerplate. It is a beacon. It is tempting to conclude that future success will follow from continuing the successful strategies of the last 130 years — that the same beacon will attract new generations of scholars and students.

That may be true, but it is equally likely that the Georgia Tech student of 2030 will be different in fundamental ways from the student of generations past. The changing landscape of a Georgia Tech education is evident to anyone who looks at the numbers. Georgia Tech is, for example, a public university that is starting to resemble a highly selective private university.

While it is still relatively inexpensive to attend Georgia Tech, tuition and fees for in-state students have increased nearly threefold since 2006.

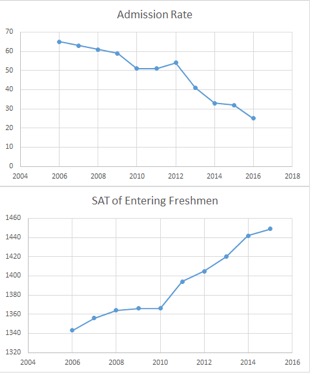

It is now a much more selective institution. In 2006, Georgia Tech admitted 65 percent of all applicants. By 2015, the admission rate had fallen to a little more than 20 percent. Over the same period, the SAT scores of entering freshmen rose from 1340 to 1440, and entering students now begin their undergraduate careers with nearly two full semesters of required coursework already completed.

In such a world, past patterns might not be the most accurate predictor of what it will take to define the technological university of the mid-21st century. Georgia Tech is a larger institution today than it was a decade ago, and despite the emphasis on sponsored research programs, the proportion of undergraduates has grown. Today’s students are older and more diverse. In a university where men have historically outnumbered women by a large margin, women now make up 41 percent of the student population. The ethnic makeup of Georgia Tech’s undergraduates has become more diverse, following demographic trends in the state and country as a whole.

The mean age of the Georgia Tech student is also changing, as the nation becomes collectively older. Nationwide, there will be fewer high school graduates pursuing postsecondary education. New offerings like the Online Master of Science in Computer Science and expanding professional education opportunities tap an underserved market in which the average student is a full 10 years older than his or her historical counterparts. As the Institute captures a larger share of this rapidly changing population, Georgia Tech students arrive better prepared and more advanced than ever before.

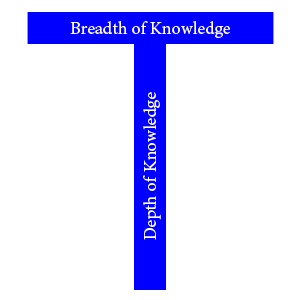

The nature of the job market for Georgia Tech graduates is also being transformed. There will be a sharp acceleration in globalization and a growing demand for “T-Shaped” professionals who combine technical depth with breadth of knowledge.

The skills of the future workplace will be influenced by increasing automation and the rise of artificial intelligence, both of which will replace jobs that in generations past would have required skilled workers.

Graduates who previously would have sought stable, long-term employment with respected companies are increasingly entering a “gig” economy in which professional careers are composites of smaller engagements, often interspersed with a return to college to acquire a new skill or a new credential. For an institution that has been centered on bachelor’s degrees for recent high school graduates, the shift toward graduate degrees and professional education means that new educational experiences have to be invented.

A traditional Georgia Tech education involves classrooms, lectures, tests, laboratories, and a stable curriculum. Innovation around these components often takes place over many decades, but rapid advances in the science and technology of learning are disrupting tried-and-true models. Technologies supplement human teaching and make more effective pedagogies accessible on a global scale. It is now feasible to deploy active learning, which is known to provide superior results, in many cases replacing passive consumption of static content. “T-Shaped” graduates require an attention to cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal skill development that is outside the purview of classroom instruction. The rapid pace of change is more easily accommodated by cocurricular creative spaces, entrepreneurial experiences, and a commitment to whole person education than a rigid syllabus listing topics to be covered day-by-day.

Continuing to define the technological university of the 21st century will require new approaches to imparting skillsets like adaptability, communication, and complex system thinking. A successful Georgia Tech graduate is more than a skills inventory. There is increased demand for graduates with mindsets like empathy, character, ethics, etiquette, curiosity, and creativity. Existing pathways will be disrupted by increased demand for flexibility in how learners enter, pause, exit, and return to a continuing college experience that is highly tailored to individual needs. A renewal of the university’s social commitment in light of changed regional, national, and global needs may be required. Political and economic forces may place as yet unforeseen demands on institutions like Georgia Tech, fraying old business models and creating new ecosystems.

Colleges ignoring these forces often face irresistible competitive pressure, declining enrollments, and costs that far outstrip the value they provide their students. Competitive success in the higher education marketplace will be the reward for those institutions that develop a culture of educational innovation and anticipate changes like these. There are dozens of initiatives to spur this kind of innovation. The University of Michigan established an Academic Innovation Fund to incentivize experimentation in new classroom methods. Stanford’s Design School sponsored a “Year of Learning” design challenge. MIT’s Office of Digital Learning is aimed at transforming teaching and learning on campus and around the world, an innovation model followed by Carnegie Mellon University’s Simon Initiative to establish a cross-disciplinary engineering education ecosystem.

Lessons can be drawn from the experience of institutions with very different missions. Olin College, for example, forges partnerships in education between students and faculty members, which reach deeply into how teaching effectiveness is evaluated. There are university-wide task forces that harness faculty talents to improve classroom instruction. Rankings now routinely incorporate innovation as a key indicator of institutional effectiveness. There are think tanks and sandboxes to spur experimentation with new ways of organizing traditional curricula and delivery methods.

Innovation often arrives cloaked in new partnerships. Agreements with content and technology suppliers might be replaced by a shared commitment to develop new content platforms for adaptive course delivery. Research universities can develop more agile relationships with community colleges and technical schools to improve the attainment levels. Accreditors and government agencies promote and reward experimentation and information sharing among peer institutions. Colleges can expand their boundaries by working with secondary schools to bridge the readiness gap that college and high schools both blame for decreasing levels of attainment.

Faced with different students, a changing socioeconomic climate, learning and teaching transformed by science, and the future workforce demands for future skills, a 21st century Georgia Tech is likely to be quite different from the Georgia Tech of the 19th and 20th centuries. Recognizing the accelerating pace of these and other changes in higher education, the Office of the Provost formed the Commission on Creating the Next in Education (CNE) and charged it with thinking boldly and broadly about the ways in which the institution, poised to enter the second half of the 21st century, can be an even more effective innovator in education. Composed of more than 50 faculty members, students, staff, and a board of external advisors, CNE has a broad charter to inquire into all aspects of the Institute that might impact Georgia Tech’s ability to prosper in a changed educational world.

In forming the Commission, the provost asked specifically for investments in innovation that can be made today to influence future planning. CNE will envision, within the context of Georgia Tech’s strengths, mission, and opportunities, the technological research university of the 21st century and will recommend pilots and projects to move Georgia Tech toward that vision. In addressing these broad goals, the Commission will consider many of the drivers of change mentioned above:

- Needs learning styles and demographics of future students

- New populations of learners and markets for post-secondary education

- Sustainability of business models and the nature of future partnerships

Many ideas will originate elsewhere, so CNE will examine best practices at peer institutions and seek out new ways to engage the Georgia Tech community in order to foster innovation. The Commission’s output will consist of recommendations for pilots, experiments, and prototypes. It will identify ecosystems that need to be formed.

In February 2016, the Commission began a discovery and data gathering phase to assemble facts and statistics about the Institute and larger global trends in higher education. A key output of this discovery phase will be activities that raise institutional awareness and provide a base of expertise for future work. After the discovery phase, CNE will engage in extended ideation exercises that build on themes identified during discovery. Ideation will lead directly to the synthesis and design phase, during which project proposals will be designed and recommendations will be made to Institute leadership.

This report on Drivers for Change is the first of a series of Commission reports that provide a window into CNE findings and activities. It consists of analysis of five major factors that will most directly affect education over the coming decades:

- Demographic trends and shifts

- Socioeconomic forces

- The changing nature of students and their learning needs

- Advances is the science of learning and teaching that can be anticipated

- How an institution organizes for deliberate evolution and development to meet the need for continuing innovation in higher education.

Armed with extensive data and a charge from the Institute, CNE will have a rare luxury: adequate time to develop ideas that might be acted upon. The mid-21st century is well beyond Georgia Tech’s current planning horizon. The Commission’s role is not to engage in premature planning but rather to consider the ideas, experiments, and novel ways of organizing that can inform future strategy. CNE will develop roadmaps that describe the events and forces that led Georgia Tech to its current point and to peer into possible futures for the Institute and higher education in general.

The Commission will lead Institute-wide discussions of fundamental questions surrounding topics such as the knowledge 21st century students should gain and how sustained lifelong learning differs from the transformational learning experience of recent high school graduates. In a sense, CNE is an opportunity to deepen the knowledge needed for the Georgia Tech community to pursue strategic “options” that can be exercised over the next 20 years.